What if you could command a robot to wash the dishes - just by thinking about it?

This isn’t just the stuff of science fiction. In Akihabara, the tech center of Tokyo, one team is working to make this a reality. The Reinforcement Learning Team at the neurotech start-up, Araya, brings together specialists in everything from robotics to neuroscience, all united by a shared mission: to create brain-robot interfaces that empower individuals with motor disabilities. We interviewed the team lead, Dr. Kai Arulkumaran, about his experience building brain-robot interfaces.

Becoming a brain-robot interface researcher

Before starting at Araya, Kai completed his PhD in Biomedical Engineering as well as several internships at top institutions including DeepMind and Facebook AI Research. Always having had an interest in neuroscience, Kai’s work frequently drew inspiration from the brain.

Early in his career, he explored using AI models to mirror human cognitive functions, such as episodic memory, within reinforcement learning algorithms. Simultaneously, he noticed the impact that the boom in deep learning was having on neuroscience. Hoping his background in AI could aid neuroscience research, he decided to move across the globe to work for Dr. Ryota Kanai, a leading expert in consciousness and CEO of Araya.

At Araya, Dr. Kanai had a vision to combine AI expertise with neurotech to enrich people’s everyday lives. After Dr. Kanai was awarded the Moonshot grant by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) in 2020, he asked Kai to lead a team to work on robot learning technology that utilized brain-machine interfaces (BMIs).

Designing brain-controlled robots

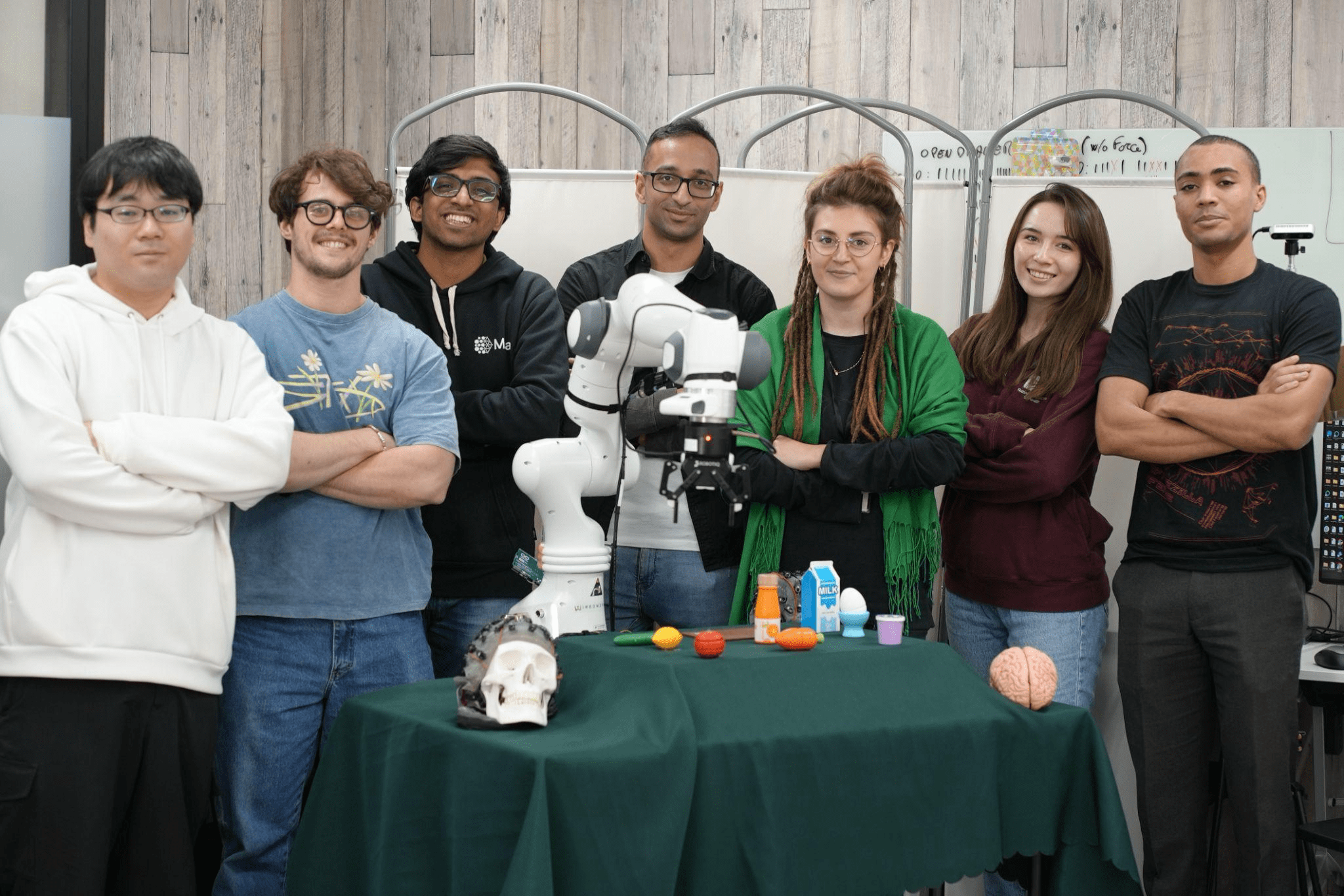

Since establishing the Reinforcement Learning Team in 2021, the team has grown rapidly, doubling in size in the last year. The new hires have allowed the work to similarly accelerate, with the team having success controlling multiple robots with pairs of human users using EEG headsets. This was accomplished by pairing EEG, EMG and eye tracking in a modular decoding pipeline to send commands to robots. Using this framework, humans were able to operate the robots and collaboratively accomplish tasks such as packing away groceries on a kitchen table. The team is currently working to extend this work to generalize to other assisted daily living tasks.

In the next few years, Kai envisions combining this system with foundation models to build general-purpose robotic assistants:

Instead of telling a robot to “open up the cabinet”, “pick up the plate”, “put the plate in the cabinet”, etc., you could just tell it to “tidy up the table”, and perhaps after a bit of clarification, the robot could just get on with it. In essence, I believe the future of brain-robot interfaces will largely depend on progress on general-purpose AI and robotics, more so than advances in neuroscience. And so that’s what the team is betting on.

Enhancing quality of life for those with limited mobility

The need for brain-controlled robotic assistants extends far beyond convenience. It’s a path to restoring autonomy and dignity to individuals with motor impairments:

If you ask people what they want AI/technology for, one of the most common responses is ‘to clean up’. We want technology to automate away the mundane tasks in our lives. And of course, people with handicaps or the elderly stand to benefit the most from such technologies. The rising elderly population makes this an even more pressing problem, with a lack of human carers. And having helped care for a relative with Alzheimer’s, I’m very much aware of how important having assistance is.

Bridging the gap between AI and Neurotech

Kai explains that neurotech is one of the many fields that could be revolutionized by AI:

[With neurotechnology], we can collect large amounts of data at high frequency and need to be able to analyze it - this is a great fit for ML

Araya has also been exploring EEG scaling laws and found that collecting large amounts of EEG data leads to a continuous increase in the accuracy of EEG decoders. If these findings generalize, it may be possible to create noninvasive BMI systems with a high bandwidth of decoded information using recent advances in AI.

Building a global team in Tokyo

With a diverse team spanning six countries, the Reinforcement Learning Team operates primarily in English. Within Araya, teams navigate a blend of English and Japanese, balancing local context with an international reach.

I want the team to be at an international level - reading and publishing papers in English - so I think it makes sense for as much communication as possible to be in English. Disseminating research in Japan in Japanese inherently limits your audience.

He explains that the language barriers are not the only communication challenges to overcome. Managing the expectations across different backgrounds was also an unexpected challenge:

Someone outside of neuroscience might see stories of people speaking again through brain implants and think that if it is possible, we should be able to do it too. And on the other hand, someone outside of robotics might see videos of robots walking around or even cooking, and assume that we could do the same. But in fact these are results from the top research labs, and replicating all of this is far from trivial. Still, that’s our goal!

Working at a start-up in Japan

Having heard horror stories about the working conditions in Japanese companies, Kai could have been hesitant about working in Japan. However, he stated he joined Araya with confidence, because he knew the start-up’s approach would be different. The company’s CEO, Dr. Kanai, who has spent considerable time in Europe and the US, has fostered a modern, open-minded environment. Kai expressed appreciation for his leadership style:

Anyone can directly question him, and he’s open to feedback, so I think that shows his strength as a leader.

There are also unique advantages to developing neurotech in Japan. Japan’s indigenous religion, Shintoism, teaches that there are spirits inhabiting all things, from mountains to pencils. This is in contrast to Abrahamic religions, which place humans as special beings above others. This acceptance of objects as potentially "alive" is thought to contribute to Japan's openness to advanced technologies, including robotics.

When growing up, it was a dream of mine to visit Japan, the land of technology. My interest in robotics started at a young age, inspired by the Honda ASIMO humanoid robot - a robot that inspired many current roboticists around the world. And even now, even if Japan isn’t seen as being at the cutting edge of all technology, the public sentiment towards advanced technology is very positive. Here, the most famous fictional robot is Doraemon, not the Terminator. In Japan, robots are seen as co-existing with and helping humanity, whereas in the West, fiction often portrays robots as the enemy of humans. And neurotech plays a large role in several popular manga, such as Ghost in the Shell and Sword Art Online, so if you want to deploy robots or BMI in society, this is the place to be.

What do you see as the killer apps of neurotech?

In the short term, the team hopes that building brain-robot interfaces will aid with everyday tasks for those with severe physical disabilities.

Any increase in what they can do represents a massive quality of life improvement. Being able to operate a computer easily is one jump in autonomy, but being able to operate a physical robot would represent another step change in what they could do.

Further in the future, Kai envisions a society where healthy people opt for neural implants as a way to measure biomarkers.

Step one is being able to monitor how our brains are functioning. Step two - being able to control objects in the physical world using our brain - that would certainly be an exciting future.