Many neural engineering labs are researching neural decoding, a process in which a decoder attempts to translate neural data into understandable information. There exists a wide range of decoders, from decoding motor control information to allow quadriplegic patients to move a robotic arm, while others have reconstructed images that subjects are looking at, solely from brain activity.

Chang Lab, led by Edward Chang of UCSF, is working on decoding speech from brain activity data, and won second place in last year’s BCI Award. We interviewed Dr. David Moses, who is working as a postdoctoral fellow at Chang Lab, and asked him about the current status, challenges, and future direction of neural speech decoding.

Reclaiming the Patient's Voice. David’s thoughts on Neural Speech Decoding

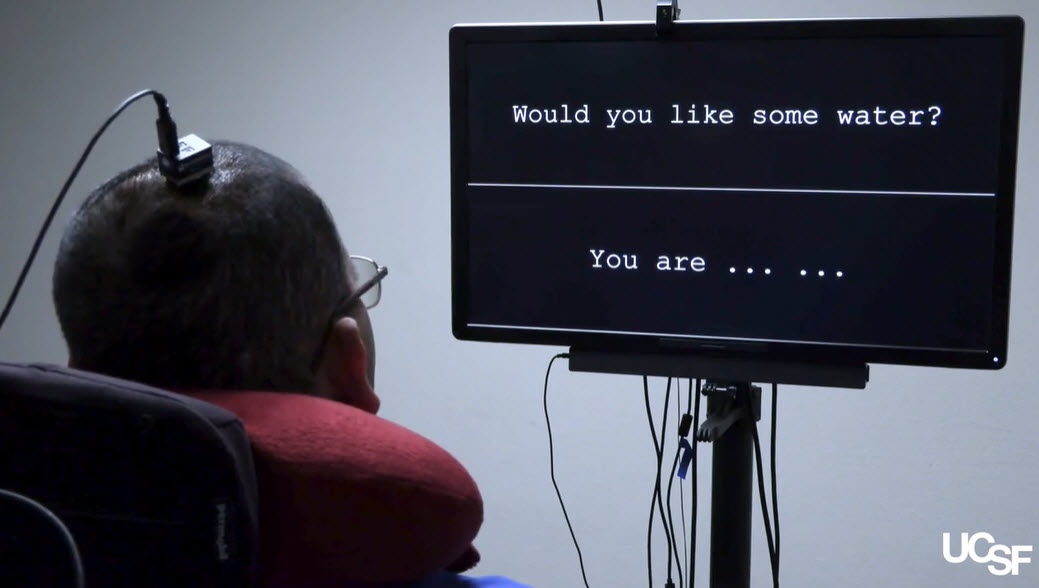

The study conducted by David’s team, successfully decoded the words and sentences that a subject with speech deficiencies attempted to speak based on brain activity recorded through implanted electrodes. The study, which won second in last year’s BCI Award, has been covered in more detail by NeurotechJP in a previous article.

Video: Explanation of the research which won 2nd place at BCI Award 2021

Video: Explanation of the research which won 2nd place at BCI Award 2021

David's other research includes utilizing the encoder-decoder model used in machine translation, and decoding speech as an answer given a question sentence. He explains how he came to be involved in such research on neural speech decoding.

I joined this lab, the Edward Chang lab at UCSF, in 2013 as part of my PhD program. Actually, I started working with speech perception. So basically, people would hear sentences, and then I would try to decode what they heard. And then over time, I ended up working more towards also trying to decode produced speech, so what someone was saying, and this is all done from intracranial recordings.

At UCSF, there are patients who visit UCSF for treatment of medically intractable epilepsy. They have seizures, they have epilepsy, but medicine does not work to to treat their condition and they need to get brain surgery. So neurosurgeons such as my boss, Eddie Chang, first perform a surgery to implant a sheet of electrodes on the surface of the brain. This technology is called Electrocorticography, ECoG, for short. From these electrodes, they record brain activity to try to find the sources of the seizure. And then, they do a second surgery where they try to resect the part of the brain that is causing the seizures. For a lot of these patients, they volunteer to participate in our research, which are speech studies. While these sensors are recording activity from their speech cortex, we are having them listen to sentences or to try to speak. And then we can try to learn a mapping between the brain activity that we record during this and the speech that they heard or produced. That is the basis for these projects that I that I did in my PhD.

Also, I had a focus on real time processing as well. I was curious about how to decode speech information in real time, as the person is speaking or hearing. That is what led to the current work.

David’s hope is to research interfaces that will improve communication for patients with speech difficulties using neural speech decoding.

All that work I just described for my PhD, was with patients who could speak naturally. But the goal of the new work that came out as part of this ongoing clinical trial is to evaluate if these approaches can work in someone who is actually paralyzed and cannot speak. For these people, it is very hard to communicate not being able to speak, they have to use other methods to communicate. And our clinical trial participants also have limb motor disabilities, so they cannot move their arms or type either. Their options for communication are extremely limited. So for me, the long term goal that is personally motivating is to be able to develop reliable technology that is practical and can restore voice to people who are unable to communicate rapidly or naturally. And it gives them an option to control their personal devices and to communicate using speech with their caregivers and their family and their friends.

Without any guarantee, the team successfully demonstrated speech decoding in speech paralysis patients for the first time.

David led the team that conducted this research.

My role was to lead this project. Dr. Chang was the principal investigator and supervised everything, and I led the effort making design decisions for the task, making sure that the data was collected and analyzed properly, writing the real-time processing software, and generally coordinating various aspects of the research and publication.

Neural speech decoding, tested on subjects without speech impairments, has been successfully demonstrated in the past; David’s study would be the first to demonstrate speech decoding from subjects with Anarthria (or complete speech paralysis). David reflected on the challenges and risks of attempting such a novel study.

There were logistical and clinical challenges of getting the trial set up and going, and recruiting the participant. I did not have a direct role in recruitment, but I know that it is very challenging to get everything set up to where we can work on this project.

When you get down to the actual approach, there were so many things that could have gone wrong. It is hard to say what the most difficult part was, but from what was known previously about the human brain and speech in someone who has lost the ability to speak, which very little was known about, it was possible for nothing to work. Just to implant these electrodes and when he tries to speak there is no discriminatory information in the neural signals, so we cannot actually tell what he's trying to say. That could have been an outcome.

Image: Overview of the expeirment (Neuroprosthesis for Decoding Speech in a Paralyzed Person with Anarthria)

Image: Overview of the expeirment (Neuroprosthesis for Decoding Speech in a Paralyzed Person with Anarthria)

Three Difficulties in Neural Speech Decoding

Chang lab’s efforts has progressed the entire field of speech decoding research, but there seems to be room for improvement in the accuracy. What exactly are the challenges that researchers must overcome to improve upon current speech decoders?

To answer this, David mentioned the following three points.

- Alignment

In terms of decoding speech when you are working with someone who cannot actually speak naturally, the big thing is, figuring out what the ground truth is. It is nice when someone can speak because you know exactly when they are saying what, but in this case, it is a lot harder to align the neural data to what you expect the behavior to be.

- Noise

And then just the inherent Signal to Noise limitations compared to, for example, trying to decode speech from an acoustic waveform. It is much harder to do so from neural activity because brain recordings are not just noisy but there are a lot of background processes that are not relevant to speech. So I think as hardware improves, like getting higher spatial resolution and coverage, we should see improvement in the ability to decode speech from brain activity.

- Generalizability

The last one I will say for now is generalizability. It is really hard to make a generalizable decoder that goes from brain activity to speech with this patient population. Our work was 50 words, but expanding that to 1000 words would require basically a new modeling approach. I would say that it's a big challenge not just decoding a small set of words, but enabling really large vocabulary decoding.

Towards practical speech: the engineering challenges of neural speech decoders

Currently, eye tracking for text input is already in market, and in some cases is it being used as a communication tool for patients with speech paralysis. However, neural speech decoding has yet to be put to practical use. When will it become available not only for research purposes but also for actual use by patients?

David says that there are still a number of problems that need to be overcome.

I think there are many hurdles. On top of the scientific and engineering hurdles, there are regulatory hurdles. It is reasonable to make sure that people that are getting brain surgeries are receiving something useful, but I think that it is going to take some time. It is really hard to put a true timeline on it. I think for people with extremely severe disabilities, getting something that improves their standard of communication via a commercial application may take a decade. It may be possible within five years, but I think it depends.

Before I feel really comfortable making some kind of claim for this, I would want to make sure that our approach can work in more than just this one person. If we see that even with different people and different disabilities we are able to decode what they intend to say to some degree, and if that degree is useful and offers increased benefit over their current non-BCI modes of communication, then I think that would accelerate my timeline.

On the other hand, Meta (formerly Facebook) was once interested in Chang Lab and provided research funding. In this regard, David said that he is not thinking of applying this technology to people without disabilities.

We are definitely not thinking about something for the average person right now. In today's day and age, it seems hard to imagine that someone would voluntarily get a brain implant for something like this, especially if they do not need it. I am not saying that it could never happen. It seems like the application would have to be capable of something inherently different than developing a speech neuroprosthesis.

From my understanding of Meta’s publicly announced goals for this, they were interested in making a non-invasive brain computer interface that would allow someone to control, for example, their smartphone without having to speak or look at it or anything. I think one of the reasons they funded us was because they believe in what we are trying to do in terms of helping paralyzed people and wanted to see how far the technology could be pushed with invasive methods, not because they wanted to do anything invasive.

But now, funding with them has ended, and they have also announced that they are now focusing more on their EMG control.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/68988252/Visual_3.0.png) Image: A wristband being developed by Meta using EMG

Image: A wristband being developed by Meta using EMG

Lastly, we asked David about his future plans.

Right now I am still focused more on shorter term goals of projects that we have going on as part of the ongoing clinical trial. So I am definitely still interested in working with paralyzed participants and trying to take this technology closer to application. It would be really interesting to see this technology developed into something that is practically useful.

In conclusion

A huge thanks to David for his insights into his research and the future of speech decoders.

At the end of the interview, we asked David for his personal opinion on some of the skills required to work at the Chang Lab. He first mentioned experience in Python and Machine Learning, bonus points for speech related projects. In terms of the neuroscience, the nature of the research at the lab does not require detailed understanding at the cellular level, but knowledge at the systems level such as the mechanisms of complex behavior control would serve to be useful.

Seeing the groundbreaking research from Chang Lab, the team at NeurotechJP is hopeful for developments that will propel us towards a world where patients with speech and motor impairments will be able to communicate again.